The Unbearable Invisibility of Being MENA in the Media

Growing up in Hawaii, despite its beautiful, multicultural communities, there was rarely a person around me that was Middle Eastern North African (MENA). My Iranian immigrant family practically took off sprinting after anyone if we heard even an inkling of Farsi spoken, just so that we could say hello. It was that rare and that coveted.

Decades later, those same combined, complicated feelings of yearning, heartache, and gratitude still wash over me when I find any media representation whatsoever that positively represents Persian culture. That’s why I was immediately diverted from my piled-up to-do list when I came across an Instagram video post of Britney Spears saying “Asheghetam” (“I love you” in Farsi) to Sam Asghari, her long-time boyfriend and now fiancé, who happens to be Iranian-American.

In fact, representation of Iranians, or anyone with MENA heritage has historically fallen short in Hollywood. Portrayals are often limited to painfully stereotyped characters which Meighan Stone, Former President of the Malala Fund, described as “negative, violent, and voiceless” in her report for the Harvard Kennedy School. In fact, her study of a 2-year period, between 2015-2017, found that there was not a single news story that highlighted positive coverage over negative coverage of Muslim protagonists.

Similarly, Jack Shaheen’s book Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People analyzed 1,000 films across more than 100 years of filmmaking (from 1896-2000) and found that a whopping 93.5% offered negative portrayals, while 5% were neutral and a sad minority of only 1% were positive. A recent study by the MENA Arts Advocacy Coalition found that 242 primetime, first-run scripted TV and streaming shows between 2015-2016 underrepresented MENA actors. When including MENA characters in primetime TV shows, a majority (78%) depicted roles of terrorists, tyrants, agents, or soldiers, most of which were spoken with an accent.

MENA actors who break through MENA stereotypes are often still hidden and invisible in terms of their MENA identity. Among those with Iranian-American heritage: Yara Shahidi, Sarah Shahi (birth name Aahoo Jahansouzshahi), Adrian Pasdar, and others whose roles are often portrayed as a character with another non-MENA ethnic background (which sometimes coincides accurately with their own mixed heritage, but does not reflect their MENA side), such as Black, Latinx or Italian American.

Not enough has improved, but there are inklings of potential progress. Although the intriguing plan to launch a comedy about a Middle Eastern family of superheroes has yet to bear out, the TBS sitcom Chad made it on air after five years in development. Chad is about a teenage boy named Ferydoon “Chad” Amani, a 14-year-old Iranian-American played by Nasim Pedrad of Saturday Night Live.

In an interview with the Hollywood Reporter, Nasim Pedrad sums up how her personal experience motivated her vision for the show:

“When I was growing up, I did not see a half-hour comedy centered around, you know, a Middle Eastern family let alone specifically, a Persian one. In fact, so much of the representation of Middle Easterners on TV that I did see was predominantly negative, which was very alienating. I didn’t see Persian people on TV that seemed anything like the Persian people that I was surrounded by, not just in my family, but in my community. I didn’t understand. I was like, ‘Why are Middle Eastern people on American television only bad guys?’ Like what about those of us living here that are just like the rest of you, except for the specific cultural elements that we still celebrate and hold onto. So my hope is that people watch the show and actually can recognize that yes, this family is Persian American, but hopefully they can tap into just how many similarities we all have and how much we all have in common.”

Psychologists and other scholars substantiate the importance of representation. The failure to move past stereotyped, negative roles for a majority of MENA characters is deeply harmful. It contributes to what my colleagues and I described as a cumulative racial-ethnic trauma for MENA Americans, in an article published in the American Psychologist. MENA Americans live with chronic and pervasive experiences of hypervisibility related to negative portrayals, and utter invisibility when it comes to featuring the positive, or even just the normal. These chronic subtle, and sometimes overt, messages of hate build up, contributing to insecurity, alienation, hopelessness, and ultimately, physical health and mortality.

In contrast, the potential benefits of media portrayals that affirm the ways in which MENA and other diverse communities are interconnected, loving, and share common values, hopes, and dreams, matter to children’s mental health and well-being. They matter to creating a society that has compassion, empathy, and embraces the many strengths that diversity brings.

Actionable Insights

Do your homework. Watch and read authentic stories. Examples in the media are when Anthony Bourdain visited Iran on Parts Unknown, or when Brandon Stanton took his camera to Iran and other countries allowing his loyal HONY following to connect with the universality of human struggles and triumphs across borders.

Represent rich complexity, identities, and varieties. Feature MENA characters in television and film with non-stereotyped characteristics and roles. Pay attention to details such as accents, religious beliefs, immigrant generation, sexuality, and gender roles that perpetuate negative stereotypes, are often inaccurate, and do not represent the diversity within the MENA community.

Involve insiders. Involve MENA Americans in content creation to ensure authenticity of stories and characters. CSS Collaborator, Sascha Paladino, and his team offer a lovely model of inclusion and authenticity in Mira, Royal Detective, a Disney Junior show featuring a South Asian protagonist.

Amplify capable, compelling, desirable representations. Amplify MENA stories that represent the many societal contributions MENA Americans make. Oftentimes, when someone with a MENA heritage does something well, their race/ethnicity is suddenly invisible from the story, and may not even be reported.

Increase the sheer number of characters. Increase the MENA American characters in children’s programming. At only about 1%, there’s no place to go but up.

Be accurate about identities. Accurately and authentically depict MENA actors as MENA (or, when relevant to their actual background and not creating conflict with the storyline, upholding their mixed heritage) characters. Likewise, such as in the case of Prince of Persia, or Dune, when characters are supposed have MENA heritage, hire MENA actors.

Professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara

Collaborator of CSS

‘In the Heights’ celebrates the resilience Washington Heights has used to fight the COVID-19 pandemic

This article originally appeared on The Conversation on June 11, 2021

With camera work that swoops from rooftops to street corners, the film “In the Heights” brings to life the dynamism of northern Manhattan’s Washington Heights neighborhood.

Directed by Jon M. Chu, “In the Heights” updates Lin-Manuel Miranda and Quiara Alegría Hudes’ Tony Award-winning musical of the same name. Set in a changing neighborhood defined by Dominicans and Latino immigrants, the film eloquently expresses the feel of a hardworking place where your block is your home and a 10-minute walk is a journey to another world.

For me, the film hit home. It brought me back to the years I spent researching and writing my book “Crossing Broadway: Washington Heights and the Promise of New York City,” when I interviewed residents, walked police patrols and dug into municipal records.

In Washington Heights, long home to a mosaic of ethnic groups, some people have recoiled from human differences and huddled up in tight but exclusionary enclaves – ignorant of their neighbors at best, nasty toward them at worst.

Other residents, street-smart cosmopolitans, learned to cross racial and ethnic boundaries to save their neighborhood from crime, decayed housing and inadequate schools. In the 1990s, their efforts turned Washington Heights, once known for a murderous drug trade, into a gentrification hot spot.

My book was released in paperback during the fall of 2019. Just five months later, COVID-19 came.

Could a neighborhood already grappling with the challenges of gentrification – a prominent theme of “In the Heights” – survive a global health disaster? And could a film conceived before COVID-19 emerged speak to a city that sometimes seems to be transformed by the pandemic?

So far – and even though Washington Heights stands out in Manhattan for its suffering due to the coronavirus pandemic – the answer is a cautious yes.

But that painful victory, won with vaccines, local institutions and local ingenuity, will be valuable only if enough can be learned from northern Manhattan’s solidarity and activism to build a healthier and more just city as the pandemic recedes.

A neighborhood rife with vulnerabilities

Like other immigrant neighborhoods confronting the pandemic, Washington Heights and Inwood – the neighborhood to its immediate north – faced serious vulnerabilities.

Immigrant labor and business acumen rescued New York City from the urban crisis in the 1970s and 1980s, when white flight, job losses, a withering tax base and high crime devastated the city.

But as my co-author David M. Reimers and I pointed out in “All the Nations Under Heaven: Immigrants, Migrants and the Making of New York,” the rebuilt city is marked by inequality. Rents are astronomic, so families in Washington Heights and Inwood often double up to make costs more bearable. In the face of an easily transmitted disease, overcrowded housing was a ticking bomb.

Residents in these uptown neighborhoods were also endangered by their jobs. In a city where many white-collar workers could work from home on their laptops, a disproportionate number of Washington Heights residents had to venture out to staff stores, clean buildings, deliver groceries and provide health and child care. As one uptown resident told me, her neighbors weren’t worrying about gaining 15 pounds – they were worried whether their next customer would infect them.

Equally troubling, many uptown residents had nowhere to run to. In more affluent neighborhoods, like the Upper East Side where I live, many people with country houses could decamp. In Washington Heights and Inwood, most people hunkered down in their apartments.

Bonds forged in mutual struggle

Nevertheless, Washington Heights and Inwood have strengths born in the hard experience of making a new home in New York.

The neighborhood has long been the destination of newcomers to the city, among them African Americans escaping Jim Crow, Irish immigrants putting behind them political and economic hardship, Puerto Ricans looking for prosperity, Eastern European Jews in flight from pogroms, German Jewish refugees from Nazism and Greeks expelled from Istanbul. In the 1970s, Dominicans fleeing political repression and economic hardship began to arrive in transforming numbers, along with a small but significant number of Soviet Jews escaping anti-Semitism.

For all their differences the German Jews, Soviet Jews and Dominicans had one thing in common: individual and collective memories of living with three brutal dictators – Hitler, Stalin and Rafael Trujillo. Such experiences were traumatic and could foster a tendency to stick to the safety of your own kind, but they also bred resilience.

Starting in the 1970s, and with cumulative impact by the late 1990s, significant numbers of these residents crossed racial and ethnic boundaries to revive and strengthen their neighborhood.

Thirty years later, when federal authority was absent and the pandemic surged, public-spirited residents – fortified by community institutions – stepped up again. In both cases, it was a clear example of what the sociologist Robert J. Sampson has called “collective efficacy.”

The community steps up

Back when the neighborhood was ravaged by the crack epidemic, Dave Crenshaw, the son of African American political activists, took action. Crenshaw set up athletic activities with the Uptown Dreamers – a youth group that combined sports, community service and educational uplift. The program gave young people, especially women, an alternative to dangerous streets.

When the COVID-19 pandemic erupted, Crenshaw built on his track record. He worked with The Community League of the Heights, a community development organization founded in 1952, Word Up, a community bookshop and arts space dating to 2011, and students from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. Together, they distributed food and masks, cleaned up grubby street corners, and got people tested and vaccinated.

Further north, the YM-YWHA of Washington Heights and Inwood, founded in 1917, built on its record of serving both Jews and the entire community. Victoria Neznansky – a social worker from the former Soviet Union – worked with her staff to help traumatized families, distribute money to people in need, and bring together two restaurants – one kosher and one Dominican – to feed homebound neighborhood residents.

At Uplift NYC, an uptown nonprofit with strong local roots, Domingo Estevez and Lucas Almonte had anticipated, during the summer of 2020, running summer programs that included a tech camp, basketball and a youth hackathon. When the pandemic struck, they nimbly shifted to providing culturally familiar foods – like plantains, chickens and Cafe Bustelo coffee – to neighbors in need and people who couldn’t go outside.

Arts and media organizations eased the isolation of lockdown. When the pandemic loomed, blogger Led Black, at the local website the Uptown Collective, told readers that “solidarity is the only way forward.” In his posts he shared his griefs and vented his rage at President Donald Trump. He closed every column with “Pa’Lante Siempre Pa’Lante!” or “Forward, Always Forward!”

Inwood Art Works, which promotes local artists and the arts, shut down a film festival scheduled for March 2020 and started “Short Film Fridays,” a weekly presentation of local films on YouTube. The organization also launched the “New York City Quarantine Film Festival,” which explored topics such as life uptown in the COVID-19 pandemic, the beauty of uptown parks and the life of an essential worker.

Dreams of a better life

Of course, Washington Heights suffered during the pandemic.

Beloved local businesses vanished. Foremost among them was Coogan’s, a bar and restaurant that was the unofficial town hall of upper Manhattan, whose life and death were chronicled in the documentary “Coogan’s Way,” which is now screening at film festivals.

Families were forced to live with unemployment, isolation and fear of infection. As the social fabric frayed, loud noise levels and reckless driving of motorcycles and all-terrain vehicles raised alarm. Worst of all, the neighborhood’s residents died at rates greater than in Manhattan overall.

In Washington Heights and the rest of New York City, the coronavirus pandemic exposed long-brewing inequalities. It also illuminated character, community, strong local institutions and dreams of a better life. All these receive loving and lyrical attention in “In the Heights.”

We live, I believe, in an era when it is important to see the strengths that immigrants and their institutions bring to our cities. This film could not have come at a better time.

Professor Emeritus of Journalism and American Studies, Rutgers University - Newark

This article originally appeared on The Conversation

How to Diversify Autism Representation in the Media and Why Intersectionality Matters

HIGHLIGHTS

• Autism is a complex spectrum that includes a variety of symptoms, and no two autistic individuals exhibit the same ones.

• White children are 110% more likely to be identified with autism than Black children and 120% more likely than Hispanic children.

• Transgender and gender-diverse individuals experience higher rates of autism in comparison to their cisgender counterparts.

Growing up as an autistic individual has been difficult for many reasons, most of which stem from my interactions with other people. One memorable instance occurred during a speech therapy session I had in middle school. Although I was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) at the age of 2 and had numerous records indicating so, my then-speech therapist insisted that there was no way I could be autistic. Why? Because I did well in school. This was not an isolated incident though: to this day, I find that many people, including professionals, are surprisingly ignorant about autistic people who deviate from the typical white male savant. I, for instance, am a woman who isn’t a savant and was able to make friends and find love.

Unfortunately, autistic people like me are not represented often in the media, where many people develop their understanding of the autistic experience. While most autistic characters are portrayed as white male geniuses (like Rain Man and The Good Doctor), the fact is, autism is exponentially more complex and diverse than what we see on-screen.

In fact, a study done in 2018 on media portrayals of ASD found that around 46% of the autistic characters on-screen had savant abilities, yet only 10% of autistic people possess these skills in real life. In reality, autism is a complex spectrum that includes a variety of symptoms, and no two autistic individuals exhibit the same ones. Further, the autistic narrative excludes many important aspects of life, such as experiences with dating and romance. Perhaps most disappointing, though, is the sheer lack of intersectionality with media representations of ASD, especially with regard to gender and race.

Connections with Gender and Sexuality

Autism affects individuals of all genders and sexualities, yet most media portrayals reinforce the aforementioned stereotypes. In an article highlighting the experiences women have with ASD, it was noted that women are expected to act “normal” while living with ASD. For instance, young women are expected to complete their studies, behave like their neurotypical peers, and pick up social cues all without supplemental aid. This can lead them to camouflage behaviors (i.e., mimic neurotypical individuals to act “normal”), ultimately delaying the proper diagnosis and treatment they need. While their male counterparts quickly receive assistance and ASD identification, women feel out of place due to society providing cis men a space to “act out”, allowing neurodirvergence to be seen rather than ignored. Furthermore, one 2020 study found that transgender and gender-diverse individuals experience higher rates of autism in comparison to their cisgender counterparts. Although there are many women and LGBTQ+ individuals on the autistic spectrum, in the rare instances where autistic relationships appear on-screen, they are almost always shown from the male, heterosexual perspective.

Fortunately, there have been recent increases in shows and movies about autism’s intersection with gender and sexuality. Atypical explores an autistic boy’s difficulties with dating and coming of age, and Love on the Spectrum includes queer representation. Everything’s Gonna Be Okay includes one female character navigating her experiences with ASD and the dating world, a role played by an actor who actually has ASD, Kayla Cromer. However, these few stories cannot capture everyone’s experiences with ASD. While Atypical discusses how to navigate romance, it once again follows the narrative of a white, cisgender, male character. Similarly, Love on the Spectrum and Everything’s Gonna Be Okay mainly consisted of a white, cisgender cast. So, while the media continues to include more women and LGBTQ+ people with autism, there must also be a push for more nuanced representations with race.

Connections with Race

According to a 2018 community report on autism, white children are 110% more likely to be identified with autism than Black children and 120% more likely than Hispanic children. Many factors influence this occurrence, such as socioeconomic status and even cultural differences. To protect against discrimination, for example, African American families often emphasize independence and self-reliance in their children; if misinterpreted by family or health care providers, these characteristics could lead to a delayed diagnosis of autism. Furthermore, these diagnostic delays can often stem from healthcare provider bias, which could then lead to doctors misinterpreting symptoms and misdiagnosing patients from underrepresented groups. And due to stigma surrounding disability in some ethnic communities, some families may struggle to reach any diagnosis or may not even accept the presence of autism. As a result, many autistic children of color do not receive the proper treatment and support they need compared to white autistic children. Further, low-income communities of color tend to watch the most TV in the US, making it more likely that these individuals will encounter the redundant portrayal of white autistic characters.

Stories featuring autistic people of color may decrease late diagnosis in these communities by reducing stigma and depicting what autism truly looks like. One great example is Pixar’s short film “Loop,” whose main character is a nonverbal, autistic girl of color. The short has been praised by the ASD community and provides a great foundation for future representations of autistic people of color. Diversifying autism in the media can help eliminate misconceptions that prevent people of color from receiving the proper identification they need.

Conclusion

Increasing autism representation in the media would be invaluable for autistic viewers, especially autistic youth. As you may expect, autistic youth tend to experience more bullying than their neurotypical peers and may face additional bullying for other aspects of their identity such as race and sexuality. It doesn’t help that the media illustrates autistic characters as unappealing or unwanted. By including a wide array of autism representation in the media, autistic youth of all ages, races, genders, and sexualities may feel better represented and understood.

Actionable Insights

Show the diversity within the autistic community by including characters of varying race, gender, socioeconomic status, and sexuality.

Directly involve more autistic people in content creation: cast more individuals on the spectrum, recruit more autistic people behind the scenes, and consult the autistic community often.

Highlight varying issues that different populations have while growing up and living with ASD, like an autistic woman’s struggle with diagnosis or person of color’s experience with cultural stigma around disability.

This article is written from the perspective of:

B.A. Psychology, Research Assistant at Developmental Transitions Laboratory

Co-authors:

CSS Intern

CSS Intern

B.A. Psychology, Research Assistant at Developmental Transitions Laboratory

B.A. Psychology, Research Assistant at Developmental Transitions Laboratory

B.A. Psychology, Research Assistant at Developmental Transitions Laboratory

On screen and on stage, disability continues to be depicted in outdated, cliched ways

This article originally appeared on The Conversation on November 2, 2020.

The #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements have forced Hollywood and other artists and filmmakers to rethink their subject matter and casting practices. However, despite an increased sensitivity to gender and race representation in popular culture, disabled Americans are still awaiting their national (and international) movement.

“Disability drag” – casting able-bodied actors in the roles of characters with disabilities – has been hard to dislodge from its Oscar-worthy appeal. Since 1947, out of 59 nominations for disabled characters, 27 won an Academy Award – about a 50% win rate.

There’s Eddie Redmayne’s performance as Stephen Hawking in “The Theory of Everything”; Daniel Day-Lewis’ portrayal of Christy Brown, who has cerebral palsy, in “My Left Foot”; and Dustin Hoffman’s role as an autistic genius in “Rain Man” – to mention just a few.

In recent years, however, we’ve seen a slight shift. Actors with disabilities are actually being cast as characters who have disabilities. In 2017, theater director Sam Gold cast actress Madison Ferris – who uses a wheelchair in real life – as Laura in his Broadway revival of Tennessee Williams’ “The Glass Menagerie.” On TV and in movies, disabled actors are also being cast in roles of disabled characters.

Despite these developments, the issue of representation – what kind of characters these actors play – remains mostly unaddressed. The vast majority of characters with disabilities, whether they’re played by actors with disabilities or not, continue to represent the same outdated tropes.

As a professor of theater and media who has written extensively on the elements of stage drama, I wonder: Are writers and directors finally poised to move beyond these narrative tropes?

Breaking down the tropes

Typically, the disabled characters are limited to four types: the “magical cripple,” the “evil cripple,” the “inspirational cripple” and the “redemptive cripple.”

Magical cripples transcend the limitations of the human body and are almost divinelike. They make magical things happen for able-bodied characters.

In many ways, the magical cripple functions like “the magical Negro,” a term popularized by director Spike Lee to describe Black characters who are usually impoverished but brimming with folk wisdom, which they selflessly bestow on existentially confused white characters.

Like the magical Negro, the magical cripple is a plot device used to guide the lead character toward moral, intellectual or emotional enlightenment. The magical cripple doesn’t learn anything and doesn’t grow because he already is enlightened.

In film, examples include Frank Slade, the blind army colonel who guides young Charlie through the perils of teenage love in 1992’s “Scent of a Woman.” Marvel’s Daredevil character is a perfect example of a magical cripple: A blind person imbued with supernatural abilities who can function above and beyond his physical limitations.

Evil cripples represent a form of karmic punishment for the character’s wickedness. One of the most well-known is Shakespeare’s Richard III, the scheming hunchbacked king.

In a 1916 essay, Sigmund Freud pointed to Richard as an example of the correlation between physical disabilities and “deformities of character.” The trope of the evil cripple is rooted in mythologies populated by half-man half-beasts who possess pathological and sadistic cravings.

More recent examples of the evil cripple include Dr. Strangelove, Mini-Me from “Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me” and Bolivar Trask in “X-Men: Days of Future Past.”

Then there are inspirational cripples, whose roles equate to what disability rights activist Stella Young calls “inspiration porn.” These stories center on disabled people accomplishing basic tasks or “overcoming” their disability. We see this in “Stronger,” which retells the story of Boston Marathon bombing survivor Jeff Bauman.

In the inspirational narratives, disability is not a fact of life – a difference – but something one has to overcome to gain rightful sense of belonging in society.

An offshoot of the inspirational narrative is the redemptive narrative, in which a disabled person either commits suicide or is killed. In movies like “Water for Elephants,” “Simon Birch” and “The Year of Living Dangerously,” disabled characters are sacrificed to prove their worth or to help the protagonist reach his goal.

These characters serve as dramaturgical steppingstones. They are never partners or people in their own right, with their own drives and ambitions. They are not shown as deserving their own stories.

The persistence of these tropes underlies the urgent need to reevaluate the makeup of writers and production teams. Who writes these parts is perhaps more important than who acts them.

Beyond the hero’s journey

There’s a reason these formulaic roles are so prevalent.

For much of the past century, Hollywood storytelling has operated according to the hero’s journey, a dramatic structure that places the white male able-bodied character at the center of the story with atypical characters serving as “helpers” to support his goals.

This narrative model has conditioned audiences to see the helpers as purely functional. The tropes based on this framework define the categories of belonging: who is and who isn’t human, whose life is worth living and whose isn’t.

The one narrative journey that historically allowed the disabled to play a central role depicted them as working toward the symbolic reclamation of their dignity and humanity. In tragic narratives, this quest fails, and the characters either die or request euthanasia as a gesture of love toward their caretakers.

“Million Dollar Baby” and “Me Before You” are two good examples of films in which disabled characters choose voluntary euthanasia, communicating the socially internalized low value of their own lives.

But what if disabled characters already had dignity? What if no such quest were needed? What if their disability weren’t the thing to overcome but merely one element of one’s identity?

This would require deconstructing the conceptual pyramid of past hierarchies, one that has long used disabled characters as props to illuminate conventional heroes.

Carrie Mathison in the series “Homeland” can be thought of as representing this new approach. Carrie, played by Claire Danes, struggles with mental illness, and it affects her life and her work.

But it is not something to overcome in a dramatic sense. Overcoming the disability is not the central theme of the series – it’s not the main obstacle to her goal. Carrie’s disability does give her some insights, but these come at a price and are not magical.

“Homeland” further breaks the mold by giving Carrie a helper who is an older white male – Saul Berenson, played by Mandy Patinkin.

As we move towards greater gender and race inclusivity at work and in the arts, disability should not be left behind. More complex, more sophisticated stories and representations need to replace the simplistic, outdated and cliched tropes that have been consistently rewarded at the Oscars.

Associate Professor of Theatre and Dramaturgy, Emerson College

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

5 ways to challenge systemic ableism during Autism Acceptance Month

This article originally appeared on The Conversation on April 21, 2021.

April is World Autism Month. It kicked off on April 2 — World Autism Awareness Day — launching a month of activities and events across the world including the Autism Speaks’ Light It Up Blue campaign. Each year, key landmarks across Canada and the globe, including Toronto’s CN Tower, Ottawa’s Peace Tower and Vancouver’s B.C. Place light up blue to promote public awareness and understanding.

What could possibly be wrong with a campaign to sensitize the public to autism?

World Autism Month and Light it up Blue have been the subject of protest from autistic self-advocates and organizations such as Ontario’s Autistics for Autistics and the national group, Autistics United Canada.

Self-advocates point to the absence of autistic leadership in awareness campaigns and describe how the powerful advocacy organizations that fund them — led primarily by non-autistic people — continue to portray autistic people negatively as mysterious puzzles to be solved. They continue to focus on cures for autism or therapies that aim to “fix” autistic people.

At first blush, it might seem that autism organizations are finally heeding the concerns of autistic self-advocates. Words such as “inclusion,” “diversity,” “acceptance” and “understanding” pepper their campaigns. Yet these organizations persist in advancing the rhetoric of autism as a burden and disorder and often exclude autistic people from leadership.

As allies, parents and critical autism researchers, we understand the dire need for awareness, advocacy and research. Findings from our Re•Storying Autism project show autistic children and adults experience higher rates of bullying, mental health struggles, misunderstanding, inferior education, underemployment and even premature death.

Families struggle with the stigmatizing effects of misunderstanding and the lack of meaningful or culturally relevant help. This is especially true for racialized autistic people and families, who face compounded forms of exclusion and harm.

Instead of communicating care or concern through awareness campaigns and lighting it up blue this year, consider learning about initiatives led by autistic people such as #RedInstead, Autism Acceptance Month and others. Here are five things that autistic people have been saying for years that require the attention of those who claim to intervene in the name of autism:

1. Awareness

The idea that “awareness” of autism is needed suggests there is widespread ignorance of the existence of autism. The explosion of autistic self-advocacy, social media presence and representation in mainstream media and television shows like Atypical suggest otherwise (though mainstream media still limits diverse representation).

Autism was once considered a rare condition, but one would have to be vastly disconnected to be unaware of it today. Instead of awareness, we need to challenge the ableism of autism awareness campaigns, advocacy and research — the persistent barriers and attitudes that value and favour able-bodied people. This devalues and excludes embodied difference, or only considers autism as something that must be “overcome.” People don’t get over autism — they live with it. And many live with it joyfully.

2. Perspective

A focus on autism awareness privileges the perspectives of non-autistic people. The organizations that support awareness such as Autism Speaks, are run mainly by non-autistic people and rarely include autistic adults.

Challenging ableism also means challenging the leadership and power of campaigns such as Light It Up Blue for autism and World Autism Day. Rather than focus on charitable organizations and “helping,” we need to turn our attention to self-advocacy, alternative activities, forms of support and research led by autistic people themselves.

3. Leadership

Much work is needed to achieve accessible and culturally relevant policies and practices for autistic children and adults, the latter of whom are frozen out of policy considerations. The continued lack of guidance and leadership from autistic people serves as a painful reminder that lives that deviate from what constitutes “normal” are only included on terms dictated by those policing the boundaries of what is considered “normal.”

Taking seriously the perspectives advanced by autistic people, means asking them what types of supports can make a qualitative difference in their lives. It means turning to the vast body of work by speaking and non-speaking people who identify as autistic. It means moving the focus away from blue lights, ribbons or other gimmicks, and working towards a sustained challenge to systemic ableism.

4. Neurodiversity

Becoming knowledgeable or informed about autism means appreciating the vast differences among autistic people and the many varieties of what it means to be autistic. Not all autistic people are alike and, thankfully, there are also many viewpoints. Troubling tropes of autism as a disorder and burden must be left behind, and replaced by a form of neurodiversity that embraces diversity.

5. Inclusion

We need to recognize and rectify the persistent exclusion of perspectives and initiatives advanced by members of Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) communities from autism awareness campaigns, as well as diagnosis and support. This includes embracing different cultural understandings of autism that depart from a western biomedical lens focused on deficits.

This April, and every month, we urge you to reconsider the meaning of World Autism Month from the perspective of autistic people themselves.

This article was co-authored by Estée Klar, a Ph.D. in Critical Disability Studies and Neurodiversity and an artist. She is the former founder of The Autism Acceptance Project in Canada (2005-10) and is presently co-collaborator with her non-speaking son/poet/artist, Adam Wolfond, and other speaking and non-speaking neurodiverse people at dis assembly: a neurodiverse arts collective.

Associate professor Disability Studies and Inclusive Education, Brandon University

Professor, health policy, disability, public policy, social movements, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

This article originally appeared on The Conversation

With a limited on-screen presence, autistic characters have emerged in another medium: fan fiction

This article originally appeared on The Conversation on December 13, 2018.

In one Harry Potter fan fiction story, Hermione Granger anxiously awaits the results from a recent test.

It isn’t her performance on an exam in a potions course that she’s concerned about. Instead, the higher-ups at Hogwarts had ordered she undergo some psychological tests. They had noticed how quickly she talked, along with her nervous tics.

Hermione eventually sees the results: “I stared at my parents, blinking my eyes. I knew the results would be here today, but I didn’t think the outcome would be like this. Asperger, the paper said.”

In this piece of fan fiction, Hermione Granger has been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder.

As scholars of fan fiction and young adult literature, we started noticing how some fan fiction authors were incorporating autism into their stories – sometimes through new characters and other times by rewriting existing ones.

Since then we’ve been collecting and analyzing fan fictions in which young writers have created characters with autism.

These amateur writers seem to be eager to create the kinds of characters they aren’t regularly seeing in the media. The Harry Potter universe, in particular, has emerged as a popular setting.

The importance of autistic characters

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 1 in 59 children is diagnosed with autism, a word that covers a spectrum of conditions that psychologists refer to as autism spectrum disorder.

How autism manifests can vary greatly from person to person. Some experience significant disability, while others experience milder forms of cognitive difference and social discomfort.

But one thing is clear: Diagnoses have increased in the past 20 years, with the National Autism Association identifying autism as the “fastest growing development disorder.”

At the same time – outside of a couple of notable examples, like Dustin Hoffman’s character in “Rain Man” and Julia from “Sesame Street” – there continues to be a dearth of autistic characters in books, television shows and films.

Yet these media portrayals are extremely important: Accurate portrayals of autism can help people understand the complexities of this condition. Nonexistent depictions – not to mention misleading ones – foster misinformation and bias.

In 2015, Sonya Freeman Loftis, an assistant professor of English at Morehouse College, published “Imagining Autism: Fiction and Stereotypes on the Spectrum,” one of the few academic studies to take up the representation of autism in fiction.

Loftis critiques stereotypical depictions of autism in a range of fictional narratives, such as the character of Lennie in Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men,” a figure whose disability is linked to sexual violence.

But she also points out that positive representations of autism spectrum disorder can actually highlight some of the strengths that those with autism possess: attention to detail, high levels of concentration, forthrightness, dedication and strong memory skills.

Activists and scholars like Loftis have argued that people diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder should be more justly and accurately understood as “neurodiverse”: If neurological faculties exist on a continuum, theirs could simply be thought of as “different” from the statistical norm.

Young writers take the lead

If major studios and publishing companies express little interest in telling stories about people with autism, who can fill the void?

Fan fictions and other forms of do-it-yourself media-making are an outlet for people to explore issues that are often missing from mass market and popular entertainment.

Some of the most famous examples from fan fiction take place in the Star Trek universe, particularly those that imagine a gay relationship between Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock. In doing so, fans were able to integrate queer plots and themes into Gene Roddenberry’s science fiction universe at a time when few gay relationships were appearing on TV.

Given the paucity of mass media representation of autism, we wondered if young people might be using fan fiction to explore this complex topic.

Beginning in 2016 – and working with University of California, Irvine graduate student Vicky Chen – we started analyzing the writings that have appeared on a hugely popular fan fiction clearinghouse.

After selecting for categories such as “neurodiverse” and “differabilities,” we noticed that a number of stories set in the Harry Potter universe seemed to have autistic or neurodiverse characters. We collected and coded these stories, and are set to publish our findings in a forthcoming essay in the Journal of Literacy Research.

Most of the stories were written by young people who have siblings, relatives or friends with autism spectrum disorder. We concluded that, while some of these characters occasionally slip into stereotypes, most of them affirm the ability of people with autism spectrum disorder to confront bigotry and speak about their own conditions.

By extension, the stories promote an understanding of autism as something that isn’t scary or horrific.

In one story, for instance, the writer creates a new character, Albus Potter, the son of Harry Potter, who is autistic and newly enrolled in Hogwarts. In the story, Albus initially has difficulty forming relationships. But he ultimately finds friends in houses as diverse as Gryffindor and Slytherin.

His overprotective mother tries to shield him from ridicule by students and even some biased faculty. But she’s challenged by others, including her husband, who suggests that “Albus can do a great many things that people have said he couldn’t.”

The ‘magic’ of autism

Why the Harry Potter universe?

We reasoned that many of these young writers are still in school and likely huge fans of Harry Potter, so the choice of Hogwarts as a common setting isn’t surprising.

But many of the young authors also linked autism to a kind of “magic” or ability that could be understood at Hogwarts as special – even advantageous – in ways that “muggles,” or normal people, wouldn’t see. In all of the stories we analyzed, everyone with autism also has magical abilities.

In other cases, autism isn’t depicted as an impairment or a challenge to overcome. Instead, it simply appears as a “difference” – a portrayal that’s aligned with the goals of those who argue that autism should be thought of as a form of neurodiversity, not as an illness or disability.

Perhaps most significantly, this research points to the ways in which young people can craft complex representations of autism that the media shies away from.

We can’t say when positive representations of autism will move from fandom to the mainstream.

But until then, these young writers are quietly doing the work to help dispel stereotypes and generate understanding – perhaps even appreciation.

Chancellor's Professor of English and Gender & Sexuality Studies, University of California, Irvine

Associate Professor of Informatics, University of California, Irvine

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

Why are sitcom dads still so inept?

This article originally appeared on The Conversation June 16, 2020.

From Homer Simpson to Phil Dunphy, sitcom dads have long been known for being bumbling and inept.

But it wasn’t always this way. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, sitcom dads tended to be serious, calm and wise, if a bit detached. In a shift that media scholars have documented, only in later decades did fathers start to become foolish and incompetent.

And yet the real-world roles and expectations of fathers have changed in recent years. Today’s dads are putting more time into caring for their children and see that role as more central to their identity.

Have today’s sitcoms kept up?

I study gender and the media, and I specialize in depictions of masculinity. In a study I did in 2020, my co-authors and I systematically look at the ways in which portrayals of sitcom fathers have and haven’t changed.

Why sitcom portrayals matter

Fictional entertainment can shape our views of ourselves and others. To appeal to broad audiences, sitcoms often rely on the shorthand assumptions that form the basis of stereotypes. Whether it’s the way they portray gay masculinity in “Will and Grace” or the working class in “Roseanne,” sitcoms often mine humor from certain norms and expectations associated with gender, sexual identity and class.

When sitcoms stereotype fathers, they seem to suggest that men are somehow inherently ill-suited for parenting. That sells actual fathers short and, in heterosexual, two-parent contexts, it reinforces the idea that mothers should take on the lion’s share of parenting responsibilities.

It was Tim Allen’s role as Tim “the Tool Man” Taylor of the 1990s series “Home Improvement” that inspired my initial interest in sitcom dads. Tim was goofy and childish, whereas Jill, his wife, was always ready – with a disapproving scowl, a snappy remark and seemingly endless stores of patience – to bring him back in line. The pattern matched an observation made by TV Guide television critic Matt Roush, who, in 2010, wrote, “It used to be that father knew best, and then we started to wonder if he knew anything at all.”

I published my first quantitative study on the depiction of sitcom fathers in 2001, focusing on jokes involving the father. I found that, compared with older sitcoms, dads in more recent sitcoms were the butt of the joke more frequently. Mothers, on the other hand, became less frequent targets of mockery over time. I viewed this as evidence of increasingly feminist portrayals of women that coincided with their growing presence in the workforce.

Studying the disparaged dad

In our new study, we wanted to focus on sitcom dads’ interactions with their children, given how fatherhood has changed in American culture.

We used what’s called “quantitative content analysis,” a common research method in communication studies. To conduct this sort of analysis, researchers develop definitions of key concepts to apply to a large set of media content. Researchers employ multiple people as coders who observe the content and individually track whether a particular concept appears.

For example, researchers might study the racial and ethnic diversity of recurring characters on Netflix original programs. Or they might try to see whether demonstrations are described as “protests” or “riots” in national news.

For our study, we identified 34 top-rated, family-centered sitcoms that aired from 1980 to 2017 and randomly selected two episodes from each. Next, we isolated 578 scenes in which the fathers were involved in “disparagement humor,” which meant the dads either made fun of another character or were made fun of themselves.

Then we studied how often sitcom dads were shown together with their kids within these scenes in three key parenting interactions: giving advice, setting rules or positively or negatively reinforcing their kids’ behavior. We wanted to see whether the interaction made the father look “humorously foolish” – showing poor judgment, being incompetent or acting childishly.

Interestingly, fathers were shown in fewer parenting situations in more recent sitcoms. And when fathers were parenting, it was depicted as humorously foolish in just over 50% of the relevant scenes in the 2000s and 2010s, compared with 18% in the 1980s and 31% in the 1990s sitcoms.

At least within scenes featuring disparagement humor, sitcom audiences, more often than not, are still being encouraged to laugh at dads’ parenting missteps and mistakes.

Fueling an inferiority complex?

The degree to which entertainment media reflect or distort reality is an enduring question in communication and media studies. In order to answer that question, it’s important to take a look at the data.

National polls by Pew Research Center show that from 1965 to 2016, the amount of time fathers reported spending on care for their children nearly tripled. These days, dads constitute 17% of all stay-at-home parents, up from 10% in 1989. Today, fathers are just as likely as mothers to say that being a parent is “extremely important to their identity.” They are also just as likely to describe parenting as rewarding.

Yet, there is evidence in the Pew data that these changes present challenges, as well. The majority of dads feel they do not spend enough time with their children, often citing work responsibilities as the primary reason. Only 39% of fathers feel they are doing “a very good job” raising their children.

Perhaps this sort of self-criticism is being reinforced by foolish and failing father portrayals in sitcom content.

Of course, not all sitcoms depict fathers as incompetent parents. The sample we examined stalled out in 2017, whereas TV Guide presented “7 Sitcom Dads Changing How we Think about Fatherhood Now” in 2019. In our study, the moments of problematic parenting often took place in a wider context of a generally quite loving depiction.

Still, while television portrayals will likely never match the range and complexity of fatherhood, sitcom writers can do better by dads by moving on from the increasingly outdated foolish father trope.

Professor of Communication, University of Massachusetts Amherst

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

How toys became gendered – and why it’ll take more than a gender-neutral doll to change how boys perceive femininity

This article originally appeared on The Conversation on December 15, 2019.

Parents who want to raise their children in a gender-nonconforming way have a new stocking stuffer this year: the gender-neutral doll.

Announced in September, Mattel’s new line of gender-neutral humanoid dolls don’t clearly identify as either a boy or a girl. The dolls come with a variety of wardrobe options and can be dressed in varying lengths of hair and clothing styles.

But can a doll – or the growing list of other gender-neutral toys – really change the way we think about gender?

Mattel says it’s responding to research that shows “kids don’t want their toys dictated by gender norms.” Given the results of a recent study reporting that 24% of U.S. adolescents have a nontraditional sexual orientation or gender identity, such as bisexual or nonbinary, the decision makes business sense.

As a developmental psychologist who researches gender and sexual socialization, I can tell you that it also makes scientific sense. Gender is an identity and is not based on someone’s biological sex. That’s why I believe it’s great news that some dolls will better reflect how children see themselves.

Unfortunately, a doll alone is not going to overturn decades of socialization that have led us to believe that boys wear blue, have short hair and play with trucks; whereas girls like pink, grow their hair long and play with dolls. More to the point, it’s not going to change how boys are taught that masculinity is good and femininity is something less – a view that my research shows is associated with sexual violence.

Pink girls and blue boys

The kinds of toys American children play with tend to adhere to a clear gender binary.

Toys marketed to boys tend to be more aggressive and involve action and excitement. Girl toys, on the other hand, are usually pink and passive, emphasizing beauty and nurturing.

It wasn’t always like this.

Around the turn of the 20th century, toys were rarely marketed to different genders. By the 1940s, manufacturers quickly caught on to the idea that wealthier families would buy an entire new set of clothing, toys and other gadgets if the products were marketed differently for both genders. And so the idea of pink for girls and blue for boys was born.

Today, gendered toy marketing in the U.S. is stark. Walk down any toy aisle and you can clearly see who the audience is. The girl aisle is almost exclusively pink, showcasing mostly Barbie dolls and princesses. The boy aisle is mostly blue and features trucks and superheroes.

Breaking down the binary

The emergence of a gender-neutral doll is a sign of how this binary of boys and girls is beginning to break down – at least when it comes to girls.

A 2017 study showed that more than three-quarters of those surveyed said it was a good thing for parents to encourage young girls to play with toys or do activities “associated with the opposite gender.” The share rises to 80% for women and millennials.

But when it came to boys, support dropped significantly, with 64% overall – and far fewer men – saying it was good to encourage them to do things associated with girls. Those who were older or more conservative were even more likely to think it wasn’t a good idea.

Reading between the lines suggests there’s a view that traits stereotypically associated with men – such as strength, courage and leadership – are good, whereas those tied to femininity – such as vulnerability, emotion and caring – are bad. Thus boys receive the message that wanting to look up to girls is not OK.

And many boys are taught over and over throughout their lives that exhibiting “female traits” is wrong and means they aren’t “real men.” Worse, they’re frequently punished for it – while exhibiting masculine traits like aggression are often rewarded.

How this affects sexual expectations

This gender socialization continues into emerging adulthood and affects men’s romantic and sexual expectations.

For example, a 2015 study I conducted with three co-authors explored how participants felt their gender affected their sexual experiences. Roughly 45% of women said they expected to experience some kind of sexual violence just because they are women; whereas none of the men reported a fear of sexual violence and 35% said their manhood meant they should expect pleasure.

And these findings can be linked back to the kinds of toys we play with. Girls are taught to be passive and strive for beauty by playing with princesses and putting on makeup. Boys are encouraged to be more active or even aggressive with trucks, toys guns and action figures; building, fighting and even dominating are emphasized. A recent analysis of Lego sets demonstrates this dichotomy in what they emphasize for boys – building expertise and skilled professions – compared with girls – caring for others, socializing and being pretty. Thus, girls spend their childhoods practicing how to be pretty and care for another person, while boys practice getting what they want.

This results in a sexual double standard in which men are the powerful actors and women are subordinate. And even in cases of sexual assault, research has shown people will put more blame on a female rape victim if she does something that violates a traditional gender role, such as cheating on her husband – which is more accepted for men than for women.

A 2016 study found that adolescent men who subscribe to traditional masculine gender norms are more likely to engage in dating violence, such as sexual assault, physical or emotional abuse and stalking.

Teaching gender tolerance

Mattel’s gender-neutral dolls offer much-needed variety in kids’ toys, but children – as well as adults – also need to learn more tolerance of how others express gender differently than they do. And boys in particular need support in appreciating and practicing more traditional feminine traits, like communicating emotion or caring for someone else – skills that are required for any healthy relationship.

Gender neutrality represents the absence of gender – not the tolerance of different gender expression. If we emphasize only the former, I believe femininity and the people who express it will remain devalued.

So consider doing something gender-nonconforming with your children’s existing dolls, such as having Barbie win a wrestling championship or giving Ken a tutu. And encourage the boys in your life to play with them too.

Assistant Professor of Human Development and Family Studies, Michigan State University

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

How a masculine culture that favors sexual conquests gave us today’s ‘incels’

This article originally appeared on The Conversation on June 6, 2018.

After the recent shooting at the Santa Fe, Texas, high school, the mother of one of the victims claimed that the perpetrator had specifically killed her daughter because she refused his repeated advances, embarrassing him in front of his classmates. A month prior, a young man, accused of driving a van into a crowded sidewalk that killed ten people in Toronto, posted a message on Facebook minutes before the attack, that celebrated another misogynist killer and said: “The Incel Rebellion has already begun!”

These and other mass killings suggest an ongoing pattern of heterosexual, mostly white men perpetrating extreme violence, in part, as retaliation against women.

To some people it might appear that these are only a collection of disturbed, fringe individuals. However, as a scholar who studies masculinity and deviant subcultures, I see incels as part of a larger misogynist culture.

Masculinity and sexual conquest

Incels, short for “involuntary celibates,” are a small, predominately online community of heterosexual men who have not had sexual or romantic relationships with women for a long time. Incels join larger existing groups of men with anti-feminist or misogynist tendencies such as Men Going Their Own Way, who reject women and some conservative men’s rights activists, as well as male supremacists.

Such groups gather in the “manosphere,” the network of blogs, subreddits and other online forums, in which such men bluntly express their anger against feminists while claiming they are the real victims.

Incels blame women for their sexual troubles, vilifying them as shallow and ruthless, while simultaneously expressing jealousy and contempt for high-status, sexually successful men. They share their frustrations in Reddit forums, revealing extremely misogynist views and in some cases advocating violence against women. Their grievances reflect the shame of their sexual “failures,” as, for them, sexual success remains central to real manhood.

The popular 2005 film “The 40-Year-Old Virgin” nicely illustrates the importance of sexual success, or even conquest, to achieving manhood, as a group of friends attempts to rectify the protagonist’s failure while simultaneously mocking him and bragging about their own exploits. “Getting laid” is a rite of passage and failure indicates a failed masculinity.

Cloaked in the anonymity of online forums, incels’ frustrations become misplaced anger at women. Ironically, while they chafe under what they perceive as women’s judgment and rejection, they actually compare themselves to other men, anticipating men’s judgment. In other words, incels seek to prove themselves to other men, or to the unrealistic standards created by men, then blame women for a problem of men’s own making. Women become threats, cast as callous temptresses for withholding sex from, in their perception, deserving men.

Entitlement

If heterosexual sex is a cultural standard signifying real manhood for a subset of men, then women must be sexually available. When unable to achieve societal expectations, some lash out in misogynist or violent ways. Sociologists Rachel Kalish and Michael Kimmel call this “aggrieved entitlement,” a “dramatic loss” of what some men believe to be their privilege, that results in a backlash.

Noting that a disproportionate number of mass shooters are white, heterosexual and middle class, sociologist Eric Madfis demonstrates how entitlement fused with downward mobility and disappointing life events provoke a “hypermasculine,” response of increased aggression and in some case violent retribution.

According to scholar of masculinity Michael Schwalbe, masculinity and maleness are, fundamentally, about domination and maintaining power.

Given this, incels represent a broader misogynist backlash to women’s, people of color’s and LGBTQI people’s increasing visibility and representation in formerly all-male spheres such as business, politics, sports and the military.

Despite the incremental, if limited, gains won by women’s and LGBTQI movements, misogyny and violence against women remain entrenched across social life. Of course not all men accept this; some actively fight against sexism and violence against women. Yet killings such as those in Toronto and Santa Fe, and the misogynist cultural background behind them, remind many women that their value ultimately lies not in their intelligence and ideas, but in their bodies and sexual availability.

Fringe men or mainstream misogyny?

Dismissing incels and other misogynist groups as disturbed, fringe individuals obscures the larger hateful cultural context that continues in the wake of women’s, immigrants’, LGBTQI’s and people of color’s demands for full personhood.

While most incels will not perpetrate a mass shooting, the toxic collision of aggrieved entitlement and the easy availability of guns suggests that without significant changes in masculinity, the tragedies will continue.

The incel “rebellion” is hardly rebellious. It signals a retreat to classic forms of male domination.

Associate Professor, Grinnell College

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

Does Hollywood Need Guns?

Guns have been an iconic prop of Hollywood storytelling since the early days of the industry. The genre of gangster movies of the 1930s could not have existed without guns, and the same for the popular TV Westerns of the 1950s. What made those stories engaging was the melding of guns with narratives that were true to their genre. Gangsters need guns just as much as the inhabitants of the Wild West. But in today’s world, the proliferation of guns is creating a crisis of major proportions. The ease with which Americans can obtain assault-style guns is turning our cities into the wild west once glorified in the Westerns of the 1950’s.

While it is difficult to disentangle the role that Hollywood storytelling has on the growth of gun use in the U.S., there is no doubt that gun use has proliferated in popular movies and TV shows, especially in crime-related genres. In our research over the past decade at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center, we have documented the rise in gun portrayal in popular PG-13 movies and TV-14 television shows. We have also shown that the use of guns in popular screen narratives is seen as acceptable by parents of children ages 15 and older when the guns are used for justified reasons. These include defending oneself or friends and family from others who pose a threat. When Bruce Willis in the Die Hard franchise shoots the bad guys even indiscriminately, he is seen as a hero worthy of emulation.

These attitudes are also observable in young viewers of these kinds of violent entertainment. In a study we conducted with late adolescents, ages 18 to 22, we found that viewing movie clips of justified gun violence was tracked by areas of the brain typically associated with approval. But when the gun violence was seen as unjustified, young people’s brains displayed a pattern more in keeping with disapproval.

We think these findings point to problems with Hollywood’s glorification of guns. Unlike other consumer products, guns are not advertised to the general public on major forms of media. You will not see an ad for a gun on TV or in popular magazines. The gun industry doesn’t need those sources of marketing when it can rely on Hollywood to feature guns as a justified form of self-defense. Not only does Hollywood promote guns, but it also increases fears of crime when it shows the need for guns as a form of protection.

We know that such portrayals are more likely to influence young viewers who are learning about the world through screen media. Research conducted in the 2000s found that adolescents who viewed a lot of films that featured smoking were more likely to initiate smoking. We do not have similar research on guns. But we have looked at changes in gun use in popular TV shows from 2000 to 2018 and found that as the proportion of gun use in violent scenes increased over that time, the proportion of homicides committed with guns also increased, especially for young people ages 15 to 24.

The film industry responded to concerns about featuring smoking in movies by reducing the use of unnecessary use of cigarettes, especially in PG-13 movies that do not restrict viewing. Why can’t the industry do the same for guns? In other words, do we really need to rely on guns to make violent stories appealing? Can’t Hollywood tell compelling stories about crime without overdoing the use of guns?

Dan Romer

Research Director, Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania

From Limiting Beliefs to Limitless Potential: How Mister Rogers and Barbie Inspired My Learning Design of a Multimedia Curriculum for Young Children

It was never my intention to pull a Mister Rogers.

Then again — was it?

As a children’s media researcher and learning designer, I’m keenly aware of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood’s pedagogical punch. In fact, I dedicate an entire class session to this show and its spin-off, Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood, in the course I teach on youth and media at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

When media are crafted sensitively, designed to meet children where they’re at and loaded with meaningful lessons, then young children can demonstrate significant learning outcomes.

Maybe this was in the back of my head when my colleagues at the Center for Scholars & Storytellers and I accepted an important challenge…

Context

Barbie, a brand first-famous for inventing 11.5-inch fashion dolls, has evolved into a cultural icon, and after 60+ years, was still the number one toy property in the world in 2020. Over the years, Barbie has had over 200 careers, nine body types, 35 skin tones, and 94 hairstyles. The brand’s slogan proudly declares: You Can Be Anything.

So, when a team of NYU researchers published data suggesting that some young children can’t be anything, and implicated stereotypes as a major reason why, Barbie took notice. The research found that, by the age of 6, many children begin to embrace limiting beliefs, specifically:

Girls stop believing that they are as smart as boys

Boys stop believing that they are as kind as girls

Girls avoid demonstrating their leadership skills

Girls and boys doubt that girls can be anything

Internalizing these beliefs can lead children to marginalize themselves and others. And there goes everyone’s chance to be anything.

Barbie labeled the space between children’s limitless potential and their limiting beliefs “The Dream Gap.” And to help close it, Barbie funds partner organizations impacting girls directly, inspires girls through meaningful content, highlights inspirational women through their role models program, and now has commissioned a stereotype-defying curriculum.

That’s where we came in.

Barbie Dream Gap Curriculum — The Original

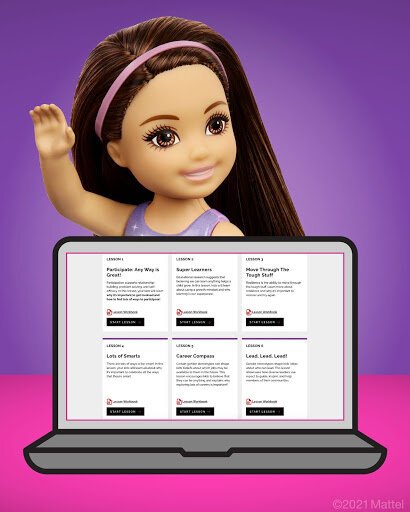

My colleagues and I designed the Barbie Dream Gap Curriculum by working backward. Our goal was to disrupt young children’s trajectories towards both stereotyping others by gender and denying themselves the opportunity to be their whole selves. Which “tools” would young children need in their “toolboxes” in order to get there?

First, we reasoned, they would need to feel empowered to authentically contribute. Lesson 1: Participation. Second, they would need to believe in their ability to learn and improve through effort. Lesson 2: Growth Mindset. Third, they would need to expect challenges and recover from setbacks. Lesson 3: Resilience. Fourth, they would need to celebrate their unique talents and interests. Lesson 4: Multiple Intelligences. Fifth, they would need to picture themselves in numerous and stereotype-defying occupations. Lesson 5: Careers. Sixth, they would need to step into their power. Lesson 6: Leadership.

To explicitly push back against harmful stereotypes, not only pertaining to gender but also to race/ethnicity, class, nationality, and ability, we incorporated the stories of diverse role models, including: Jovita Idár, Helen Keller, Junko Tabei, Fred Rogers, Maggie Lena Walker, and Annie Dodge Wauneka.

Our curriculum organically intersected with multiple social and emotional learning (SEL) goals. Research shows that universal, school-based SEL programs benefit K-12 students across a variety of measures in the short- and long-term. So, we aligned our curriculum to SEL standards.

We formatted the curriculum as a K-2 teacher-facing collection of lesson plans, worksheets, and newsletters, with an original, live-action video and a poster accompanying each lesson.

In our 2019 pilot in El Segundo, California, the curriculum demonstrated promising results. Independent evaluators conducted a classic experiment, collecting pre- and post-test data from intervention and control groups. Findings showed that the curriculum:

Expanded children’s interest in more careers

Increased all girls’ beliefs that anyone could be a good leader

Inspired more 2nd grade girls to identify females as “really really smart” and to say YES to the question, “Do you think you can be anything?”

To say I was excited would be putting it mildly. First, El Segundo. Next, the world!

Then a little something unexpected happened in 2020... Perhaps you can recall…

Barbie Dream Gap Curriculum — Take Two

Barbie challenged us to adapt the curriculum for online learning. In digital form, the lessons could reach remote and hybrid learners as well as support diverse educators.

We reimagined our curriculum as a video series featuring Community Club, an after-school club whose members yearn to help people and animals and fix things in their communities. Community Club meets online, via a video conferencing platform like Zoom -- and the students viewing the content just stumbled into its meeting. Welcome to Community Club! We split each lesson (aka, each Community Club meeting) across three videos, separated by two interactive opportunities where students could answer a question by clicking on an icon.

Channeling my inner Rogers, I played Dr. Rachel Klein, the club’s warm-and-fuzzy advisor. In that role, I facilitated many of the same activities as our original lesson plans. I also created three characters to populate Community Club’s membership:

Jada, an inquisitive, independent third-grader who identifies as a Chinese-American girl and manages anxiety;

Lulu, a thoughtful, methodical third-grader who identifies as a Black girl and as “quiet,” or introverted; and

Mateo, a gentle, collaborative third-grader who identifies as a Mexican-American boy and lives with hearing loss.

These characters were brought to life by bespoke hand and rod puppets, each operated by a puppeteer and separately voiced by an actor whose identity matched that of the character.

Educators and students nationwide piloted the curriculum this spring — thank you to participating schools in Boston, Chicago, and Austin! So far, we’ve gotten lots of positive feedback.

“I felt that the lesson was well thought out and kid friendly.”

“Loved the video with the student leader. It is so helpful for students to see the ideas in action. Also, really wonderful for them to see themselves reflected in the people in the video.”

“It was very beneficial how the puppets shared how they cope with differences, hearing loss and anxious thoughts.”

We will continue piloting the curriculum this summer — thank you to participating after-school organizations in South Carolina! — and in the fall. We look forward to combing through the data and discovering whether/how this multimedia experience serves children.

As to bridging The Dream Gap… Mr. Rogers once said, “There's a world of difference between insisting on someone's doing something and establishing an atmosphere in which that person can grow into wanting to do it.”

So, our work does not end at curriculum. Here’s to all of us, in our own unique ways, establishing an atmosphere, a society, a world that inspires everyone to want to unlock opportunity — so our kids can be anything.

Principal, Laurel Felt Consulting

Lecturer, USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

Senior Fellow, Center for Scholars and Storytellers

P.S. This project was a labor of love for so many people!!! To quote Fred Rogers, “I hope you're proud of yourself for the times you've said "yes," when all it meant was extra work for you and was seemingly helpful only to someone else." I am beyond grateful and humbled by your brilliance.

THANK YOU:

Maggie Chieffo, Yalda T. Uhls, Hannah Demetor, Kathryn Lenihan, Kim Wilson, Colleen Russo Johnson, Josanne Buchanan, Rosie Molinary, Mary Faber, Benari Poulten, Hand to Mouth Creative, Jenn Guptill, Katie O’Brien, Jaz Nannini, Students of Spring 2021 COMM 457, Sarah Berman, Chris Patstone, Miles Taber, Karen Barazza, Jenny W. Chan, Whitney Watters, Adam Blau, Gaby Moreno, Deborah S. Craig, Rebecca Naomi Jones, Nir Liebenthal, Page Spencer, Caroline Fung, Annie Meyers, Zach Stuckelman, Sina Zakeri, Anita Narkhede, Arelyse Campos, Rebeca Ruiz, Tina Garoosi, Gillian Jewell, Jill Shinderman, Kat O’Brien, Corinne, Everett, Mike Colby, Sasha, Andrea Merfeld, Lexi, Randi Ralph, Molly, Annie, Cyndi Otteson, Quinn, Ellie Chadwick, Richie, Kimmi Berlin, Ari, Diomaris Safi, Mila, Miry Whitehill, Ruben, Rebecca Fox, Ruthie, Muriel, Gardenia Spiegel, Koa, Rachel Deano, Jada.

How Narratives in Video Games Affect Children and Adolescents

As the video game industry grows, so does the need to understand its consumers and investigate its content on those consumers. Research suggests that over 90% of children and adolescents in America play video games and that the frequency of video gaming increases around age 18, peaking in an individual’s twenties.

Video games offer insight into individual characteristics and judgment alongside offering advantages in learning environments and social education as they expose players to modeling techniques through rehearsal and reinforcement of social behaviors found through the games’ narratives. These themes can vary greatly from game to game and their content has been shown to impact our cognition and behavior.

Adventuring has a powerful effect on individuals’ perspectives and psyche. Games teach us morals and allow us to explore aspects of ourselves that would otherwise be unexplored.

“A sword wields no strength unless the hand that holds it has courage.”

Allowing players the ability to project certain aspects of their psychological attributes to their avatars allows them to become the hero and experience themselves in a world where they can achieve feats beyond what is possible in their real lives. This allows a sort of power of resilience within a player without them being aware of the positive cognitive effects that are occurring as they triumph through lands and save the world from utter disaster.

Many video games are essentially moving narratives where the player gets to make decisions about what a character does next in the game. This essentially creates a virtual reality where players can learn from mistakes made in the game or learn more about themselves through the character they bring to life. Some games have fixed narratives, but increasingly, games are allowing for a more autonomous and whole version of the characters in their games. Games like “Skyrim” and “World of Warcraft” allow players to decide throughout the game whether to take a virtuous path of heroism, or a darker path of thievery, or assassination, along with other characteristics.

Basically, these games allow you to play someone you never could be in real life and this element of choice is what makes video games such an intriguing form of media. I believe Grizzard et al. 2014 said it best: “In narrative media, viewers simply watch moral decisions being made by others, but in video games, players often make the decision to be moral (or immoral).” It is also what makes researching them so complicated and intertwined. Researchers have found that individuals who engage in prosocial gameplay tend to have more prosocial thoughts and behaviors and that individuals who play more violent narratives tend to have an increase of aggressive and hostile behavior and thoughts. Ambiguous games present a unique problem and discussion for researchers.

Morality and Character Content